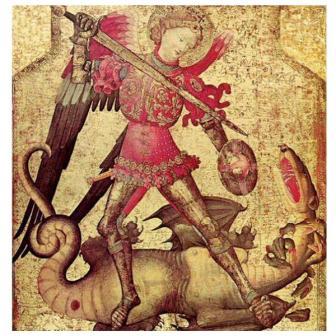

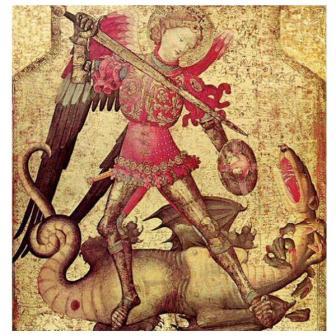

The beating of a drum warns of the coming of the dragon. Through the trees we can see its shape moving swiftly toward the field where we are standing. As the ugly head rushes into the clearing, pandemonium breaks loose and children scatter to and fro to escape the foul beast. Then, the piercing call of a single trumpet summons the Archangel Michael. Atop a white horse, he rides carrying a flaming sword. His helmet and armor of gold glimmer in the catches of the late afternoon light. With his mighty sword, he tames the dragon.

Singing praises, we gather around the Protector of Life and celebrate with a feast. All the fruits of the harvest are gathered and tables of food are prepared under the autumnal sky. When the light has grown dim and bellies are full, the crowd departs; each into their own home. Winter is coming and it is time to go inside. That was one Michaelmas celebration I remember during the years I spent living in an Anthroposophical Community for children with special needs. Being unfamiliar with Michaelmas, I wondered about its origin and meaning. St. Michael is one of the four Archangels found in the book of Revelation (Rev. 12:7). In ancient Chaldean/Babylonian mythology, he was called Marduk, the angel who killed the dragon Tiamat and created heaven and earth from its body. The Hero of the Sun or Protector of Life are two names given to St. Michael.

Singing praises, we gather around the Protector of Life and celebrate with a feast. All the fruits of the harvest are gathered and tables of food are prepared under the autumnal sky. When the light has grown dim and bellies are full, the crowd departs; each into their own home. Winter is coming and it is time to go inside. That was one Michaelmas celebration I remember during the years I spent living in an Anthroposophical Community for children with special needs. Being unfamiliar with Michaelmas, I wondered about its origin and meaning. St. Michael is one of the four Archangels found in the book of Revelation (Rev. 12:7). In ancient Chaldean/Babylonian mythology, he was called Marduk, the angel who killed the dragon Tiamat and created heaven and earth from its body. The Hero of the Sun or Protector of Life are two names given to St. Michael.

Michaelmas correlates to festivals in ancient cultural/religious traditions. The Festival of the Harvest , usually held in late September, is common among all cultures with an autumnal harvesting time. The Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur is also connected to Michaelmas. Yom Kippur is the culmination of the Jewish high holy days of Rosh Hashanah meaning, “head of the year,” the time of the Jewish New Year. It is a time of self-reflection and evaluation of one’s moral quality: a spiritual new year. It is no accident that the tradition falls during the constellation of Libra (Sept. 23 – Oct. 22) in the zodiac. Libra is the sign of the Scales signifying a weighing of one’s deeds. Deeds are the proverbial fruit of the harvest being gathered in for the winter of the soul. As we bring in the harvest in preparation for winter, we must ponder the deeds we have accomplished.

Michaelmas has great significance in connection to the symbol of the scales. Michael is often depicted holding a scale in religious iconography. There is a meaning here regarding the balance between the expansiveness of summer and the contractedness of winter. This is the time of the fall equinox when days and nights are equal lengths.

Chalkboard drawing by Abby Wright, WSA teacher.

The archetypal drama between the horse & rider and the dragon has its symbolism, too. The horse & rider is the representation of a pure soul (horse) guided by its ego (rider). This is not a self-seeking sense of ego, but rather an image of spirit power, which gives us the will to do in the world. In the same way that the rider guides the horse on its path, spirit guides the soul. The sword is directly connected to the symbolism of spirit power because of the iron from which it is made. Physiologically, if the iron level in our blood is too low, we experience a lack of energy (will power). Anthroposophically speaking, iron is viewed as the carrier of spirit power in our bodies. As it so happens, the atmosphere of the earth experiences a barrage of meteor showers every year during late August which can be seen as the universal iron permeating and strengthening the earth. The dragon is the representation of evil in the world. Evil, in the sense, can be understood as an impediment to spiritual growth: i.e. fear, doubt, impatience, hatred, rage, etc. The struggle between the horse & rider and the dragon is the archetypal struggle between good and evil.

Each of us, in our own lives, experiences the battle between good and evil every day. People on a spiritual path are concerned with personal growth as a path of development. Forces that inhibit this growth are the dragons of our lives. Often we feel a need for heavenly assistance to battle these spiritual burdens so that we may continue to grow.

St. Michael is the spiritual representation of one who understands the paradox in the relationship between the light and the darkness; between growth and hardship; between good and evil. He shines the light of truth on the darkness of falsehood, which would enslave us, but understands that it is this very light that creates the darkness. The radiant brilliance of good casts the tenebrous shadow of evil. Light cannot exist without darkness.

With this understanding it becomes necessary to face the dragon as a part of ourselves which is necessary, but not permanent. St. Michael leads us in battle against our own dragons with the light of truth and love as our guide. He imbues us with courage to face the hardships of our lives. Rudolf Steiner once said about the Michaelic impulse in the world: “The Michael force, which must completely change the ways of life of people, must find expression in great Michael festivals. This must be our goal, that the awakening of life; planting seeds of the festivals of hope, in festivals of expectancy, in festivals where the only bond is through hope and expectancy, be experienced…and not through sharply outlined ideals…Communal experience is required in order to work towards a Michael festival where the spirit of expectancy, can live.” (Breslau, June 9, 1924)

3rd Grade Teacher

This article was originally published in the December 2010 Garden Breeze newsletter of the Waldorf School of Atlanta.